Verse two, comin with that Olde E brew

Meth-tical, puttin niggaz back in I.C.U.

We left Lake Mburo and headed towards the Rwandan border. At the crossing, men with wads of Rwandan Francs approached the SUV looking for a deal. I disembarked and officially signed us out of Uganda in a small tin-roofed shack. On the other side we got our passports stamped and assured Rwandese officials that we hadn’t come from Ebola-infested Bundibugyo.

I expected to find in Rwanda a slightly degraded version of Uganda; I assumed that visible traces would remain of the genocidal civil war 13 years ago during which 1 out of 10 people were murdered by their neighbors. Instead, we drove into a superficially upgraded version of Uganda. The homes and people looked much the same, but there were differences presumably due to the efficiency of a near totalitarian government in a small country: smooth roads free of potholes, motorcyclists wearing helmets, hedges along the hills to prevent erosion. Less easily explicable, people’s gardens were more colorful and well-tended.

All along the road people walked in twos and threes, uphill and downhill. Many carried water in those still-ubiquitous yellow plastic jugs. My co-pilot, L, claimed that the rolling green hills behind them have twins in China.

To reach Akagera National Park we turned onto a descending dirt road. By that point we’d been in the SUV long enough for a vague sensation of the U.S.A. to have settled into my skin, perhaps linked to an anesthetic pumped out by the A/C. I ate cookies and spoke unrestrained American English. The Grateful Dead sang of sharing women and wine. We rambled on contentedly in our metal and plastic cocoon.

In my contented daze I noticed something peculiar about yet another group of people walking on the side of the road. It was larger than the others and moving with haste. A few people together carried something of considerable weight. I stopped chewing long enough to dumbly mumble “Wonder what’s going on there…”

L, a physician with experience in rural Zimbabwe, recognized the situation instantly. “Someone is sick. They’re carrying him to the hospital.”

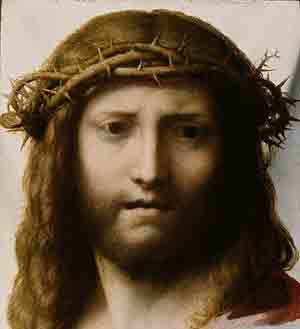

“They’re walking to the hospital we passed ten minutes ago? Jesus. It’s uphill the whole way.”

“You want to go back and give them a lift?” The idea hadn’t occurred to me. Did Newton’s Laws permit us to reach behind the windshield-shaped TV screen and pull someone into our 15-miles-per-gallon living room? Confucius smirks:

Seeking a foothold for self,

love finds a foothold for others;

seeking light for itself,

it enlightens others too.

To learn from the near at hand

may be called the clue to love.

I slowly lowered my foot onto the brake pedal. “Uh…yeah…yeah…we should go back and give them a lift. It would be the Christian thing to do.”

We turned around and pulled up alongside the crowd of about twenty people. Four young men in the lead carried a stretcher made of bamboo and palm leaves on their shoulders. A human form sagged inside. I rolled down the window and leaned out as if to request a cheeseburger with fries, biggie-sized, and large Coca-cola with extra ice. Rwandese unhappy meals came rushing in: heat, odor, panicked voices. I addressed the nearest stretcher-bearer:

“Parlez-vous Anglais?” No response.

I tried an alternate method.“Ogenda wa?” [Luganda: Where are you going?] Nothing.

Then, in my impersonation of a French accent, “Hospital?” Affirmation all around.

We got out of the car and set about clearing the back seat of all luxury: a box of books and CDs, name brand backpacks, head lamps, extra shoes, a 2 liter 7-Up bottle, L’s toiletry bag containing no less than ten tubes of various creams and lotions. During this process she somehow ascertained that the woman in the stretcher, the woman now being held up on wobbly legs by two men, was pregnant, with apparent complications. L laid a pathetically small dish towel on the backseat and said “We may have to deliver in the car.” Right. I’ll be ‘round back having an upchuck.

A team of four hauled the pregnant woman into our improvised ambulance. She half-sat, half-lay in the middle of the back seat, supported by a woman who could have been her older sister. Next to them, crammed farthest inside, a barefoot man in a sport coat decided for unknown reasons to crawl across everyone to exit rather than open the door to which his back had been pressed.

With three people and the mother-to-be remaining inside the vehicle, we were ready to roll. I gently closed the back door, climbed behind the steering wheel and, leaning forward, accelerating gently, began the meandering climb up to the hospital. A quick calculation of the risk of flipping the SUV or plunging into the roadside drainage ditch or plowing over small children on swervy bicycles versus the urgency of transporting a grimacing woman full of baby and baby juice to the delivery room yielded an optimal speed of 50 km per hour, plus or minus ten.

I accelerated less gently. L turned around in her seat to say “It’s OK, Mama.” Mama moaned. I glimpsed her head being stroked in the rearview mirror.

We reached the first of several goddamned speed humps. Mama moaned louder. Children shouted “Muzungu! Muzungu!” oblivious to our precious cargo.

The drive was taking longer than I’d expected. “How far back is the [Shoulder Angel: “Don’t say ‘goddamned’”] hospital?”

“It must be just ahead. We can’t miss it – it’s too big.”

My foothold on the gas pedal deepened further still. Energetically waving kids faded into clouds of dust. A white sedan came flying down the hill and I honked it over to where the other lane would have been, had there been lanes.

“There’s the hospital,” I said as I missed the turn. Throwing the vehicle into reverse, I let the engine stall out. “Jesus Christ.” [Shoulder Demon: “Let him have it, motherfucker!”] Eventually we came to halt under the awning of the hospital entrance.

Scanning the many faces milling about the entryway, I was comforted by the sight of a woman with a nametag. “Hello” I said.

“Hello” she answered back. Praise the Lord.

“This woman is pregnant,” I said.

Suddenly another name-tagged individual appeared, a rather burly fellow in a navy blue clinician’s coat. “You need to move your vehicle.”

“This woman is pregnant,” I repeated.

“You need to move your vehicle forward.” He gestured to the drain running under the SUV. I had no idea what he was talking about.

“Can we take out the pregnant woman first?”

The parking attendant posing as a medic then moved past me and actually managed to shut the door on Mama’s legs as her friends were helping her out. At this L’s nostrils flared, but she retained her professional calm. Annunciating carefully, she said, “Please put this woman in a wheel chair and then we will move the vehicle.” He continued to point to the drain while someone else arrived with a wheelchair. Mama slid into it and was immediately whisked into the building, her friends following closely behind.

We finally moved the vehicle forward and then just kept right on going, back down the winding hill, over the humps, past the people and homes and storefronts, and into the unpopulated savanna of Akagera National Park. Over the next two days we did what you do in a game park while Mama did what you do in a delivery room. I looked to my distant cousins for the answers to all of this. To the zebra: “Where did you get your stripes?” To the giraffe: “Why is your neck so long?” To the buffalo “How did you get so thick?” But only the hippopotamus gave me a response.

“Hippo, why you so phat?”

Yo I gets rugged as a motherfuckin carpet get

And niggaz love it, not in the physical form but in the mental

I spark and they cells get warm

I'm not a gentle, man, I'm a Method, Man!

Baby accept it, utmost respect it

(Assume the position) Stop look and listen

I spit on your grave then I grab my Charles Dickens

"Let there be IKEA."

"Let there be IKEA."